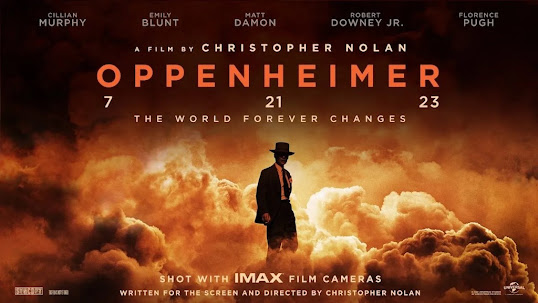

The Power of the Peace Movement vs. The Folly of Scientists: A Quaker Perspective

My wife and I went to see “Oppenheimer” with some friends and were deeply moved by its complex

portrayal of the “Father of the Atomic Bomb.” Oppenheimer’s story is profoundly

tragic, as most war stories are. He is portrayed with all his ambiguity:

brilliant, full of hubris, and morally conflicted. He realizes too late that he

has released the genie of mass destruction from its bottle, and his effort to curtail

the consequences of this act of hubris leads to his political downfall.

The movie

assumes that the dropping of the bombs on Nagasaki and Hiroshima was a

necessary evil to end the war with Japan and saved countless lives. This claim

has been disputed by “revisionist” historians like Gar Alperovitz, author of “The Decision to Use the Atomic

Bomb,” and a former fellow of King’s College, Cambridge, and Martin J. Sherwin,

professor of history at George Mason University and author of “Gambling With

Armageddon: Nuclear Roulette From Hiroshima to the Cuban Missile Crisis.”

In 2020 these historians

wrote an op ed piece in the LA

Times showing that even the military questioned the necessity of using the

atomic bomb on Japan.[1]

The National Museum of the U.S. Navy in Washington, D.C., states unambiguously on a plaque with its atomic bomb

exhibit: “The vast destruction wreaked by the bombings of

Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the loss of 135,000 people made little impact on the

Japanese military. However, the Soviet invasion of Manchuria … changed their

minds.” Furthermore, the authors point out that “seven of the United

States’ eight five-star Army and Navy officers in 1945 agreed with the Navy’s

vitriolic assessment. Generals Dwight Eisenhower, Douglas MacArthur and Henry

“Hap” Arnold and Admirals William Leahy, Chester Nimitz, Ernest King, and

William Halsey are on record stating that the atomic bombs were either

militarily unnecessary, morally reprehensible, or both.

What the movie portrays instead is

the frenzied jubilation of most Americans when they learned that the atomic bomb

had been dropped on the Japanese, who surrendered the next day. In a dramatic scene,

Oppenheimer boasts that the bomb has been dropped on the Japanese, and should

have dropped on the Germans, and everyone applauds wildly. During the deafening

and uncontrollable applause, Oppenheimer has a horrific vision of the room

consumed with atomic fire. This ambivalence is what makes Oppenheimer a tragic

figure, and the movie worth watching.

The movie ends on an apocalyptic

note, with Oppenheimer realizing that he has started an arms race that could

lead to the destruction of all life on the planet.

The power of the atomic bomb is seen

as god-like through the eyes of Oppenheimer and also the film maker, Christopher

Nolan. In a best-selling biography of Oppenheimer, Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin

compare him to Prometheus, the Greek god who gave humans fire and was punished

by Zeus by being chained to a rock and tortured for eternity. Oppenheimer names the first atomic test “Trinity,”

in reference to a poem by John Donne called “Batter my heart, three-personed

God.” When Oppenheimer witnessed the awesome power of the atomic bomb, he recalled

a line from his favorite scripture, the

Bhagavad-Gita: “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.”

In reality, Oppenheimer is all too human. His efforts to prevent the US from

building hydrogen bombs prove ineffective. He never expressed regret for having

developed the atomic bomb or its use against Japan; and rather than consistently oppose the

"Red-baiting" of the late 1940s and early 1950s, Oppenheimer

testified against former colleagues and students, before and during his hearing.

He symbolized for many the folly of scientists who believed they could control

the use of their research, and the dilemmas of moral responsibility presented

by science in the nuclear age.

I’d like to contrast this tragic and morally ambiguous story with

that of the unsung heroes of the peace movement who helped to end the Cold War

and reverse the arms race. I am thinking of Albert Bigelow, a naval commander

who had a change of heart after he went to Hiroshima and witnessed the devastation

caused by the atomic bomb. He quit the Navy a month before being eligible for a

pension, joined the peace movement and became a Quaker. In 1958 he set sail on

a boat aptly named “The Golden Rule” with the intention of entering the nuclear

test site in the Marshall Islands. He and his crew were arrested in Hawaii, but

his action inspired others like Earl and Barbara Reynolds and Greenpeace. What

a great movie his life would make!

The American Friends Service Committee and the Quakers began

reaching out to the Soviets in the early 1950s to build trust and dispel stereotypes,

with the hope of ending the Cold War. They persisted in this effort for the

next thirty some years and in the 1980s their efforts bore fruit. When

Gorbachev came to power, he wanted an end to the Cold War and the nuclear arms

race. Reagan was a staunch anti-Communist and Cold Warrior, but he was willing

to meet with Gorbachev, thanks in part to pressure from the peace movement.

The Nuclear Freeze movement not only garnered the support of

most American peace organizations but also was endorsed by numerous public

leaders, intellectuals, and activists. Former public officials, such as George

Ball, Clark Clifford, William Colby, Averell Harriman, and George Kennan, spoke

out in favor of a nuclear freeze. Support also came from leading scientists,

including Linus Pauling, Jerome Wiesner, Bernard Feld, and Carl Sagan.

Reagan was also influenced by the “citizen diplomacy

movement,” of which I was a part. Because of glasnost, Gorbachev’s

policy of “openness,” thousands of Americans went to the Soviet Union to meet

the Russians, build relationships and advocate for peace. This had a profound

impact on Reagan and Gorbachev. They eventually met at the Reykjavík

Summit in October 1986, and came very close to agreeing to ban all nuclear

weapons by 2000. Both men wanted nuclear abolition, but the American

generals persuaded Reagan not to go that far. While Reagan and Gorbachev didn’t

ban all nuclear weapons, their meeting paved the way

for the 1987 INF (Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces) and the 1991 START I

(Strategic Offensive Arms Reductions) Treaties, as well as limitations on

nuclear testing. There were over 60,000 nuclear weapons in the world

in the 1980s, and today there are 12,500. Far, far too many, but this reduction

wouldn’t have happened without the peace movement.

Hollywood buys

into the myth that Great Men are the ones who make history, but I believe that lasting

and positive change usually happens at the grass roots. I agree with Margaret

Mead who said, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens

can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.”

As people of faith, committed to peacemaking, we shouldn’t underestimate our power. Around the world there

are thousands of groups like ours working for peace. Our efforts are generally

not reported in the media or portrayed in movies, but we are nonetheless

influential. I believe that with God’s help, we can change the world for the better. As Quakers say, we just need to be "persistent, passionate, and prophetic."

Anthony M. Thank you for your considerably well researched, thoughtful review of the recent tragically dark film Oppenheimer. I would like to share your writing on my FB page. Please let me know if rhis would be okay? In the light, Roberta Llewellyn

ReplyDeleteThank you Anthony M. For tour considerably well researched and thoughtful review of the dark film Oppenheimer. I would like to share this on my FB page with your permission? In the Light, Roberta Llewellyn

ReplyDeleteThanks for your kind comment. Please feel free to share this post or any other of my posts on your Facebook page.

ReplyDeleteGood review. I would also like to share it.

DeletePeace,

Forest Preston

This is a wonderful review. Thank you, Anthony, for your deeply thoughtful and well presented article.

ReplyDelete